Do you wish to be great? Then start by being.

St Augustine of Hippo.

Is anyone reading this? Will you get to the end? Why are you here? Where is here?

Education has always sought to be life changing whether conceived as an idealistic activity or one with the practical purpose of preparing us for leisure or work. Depending on the social climate it fulfils a function which is variously utilitarian or utopian. In some parts of the world (and for girls especially) education remains a luxury, for others it is a post-industrialized necessity in part designed to keep young people off the streets and benefits. Equally, the status of teaching is variable: to teach has been seen at times as a profession only suitable for women or feeble men, at other times as a noble calling, a vocation, something of intrinsic worth and valued because it transforms lives and fortunes.

The history of education in Britain is fascinating because the notion of education as a universal right is relatively new and was not established until the Butler Act in 1944. Before that to be educated was the preserve of the wealthy and was predominantly a male enclave. In the nineteenth century when the industrial revolution was changing population patterns the Bishops of England led a partnership with the state which laid the foundations for education for all which was free. In 1847 [1], the Catholic Poor-School Committee established a unique link with the state. Fuelled by immigration in the big cities and industrial areas there was a growing Catholic population and the goal was to provide elementary education.

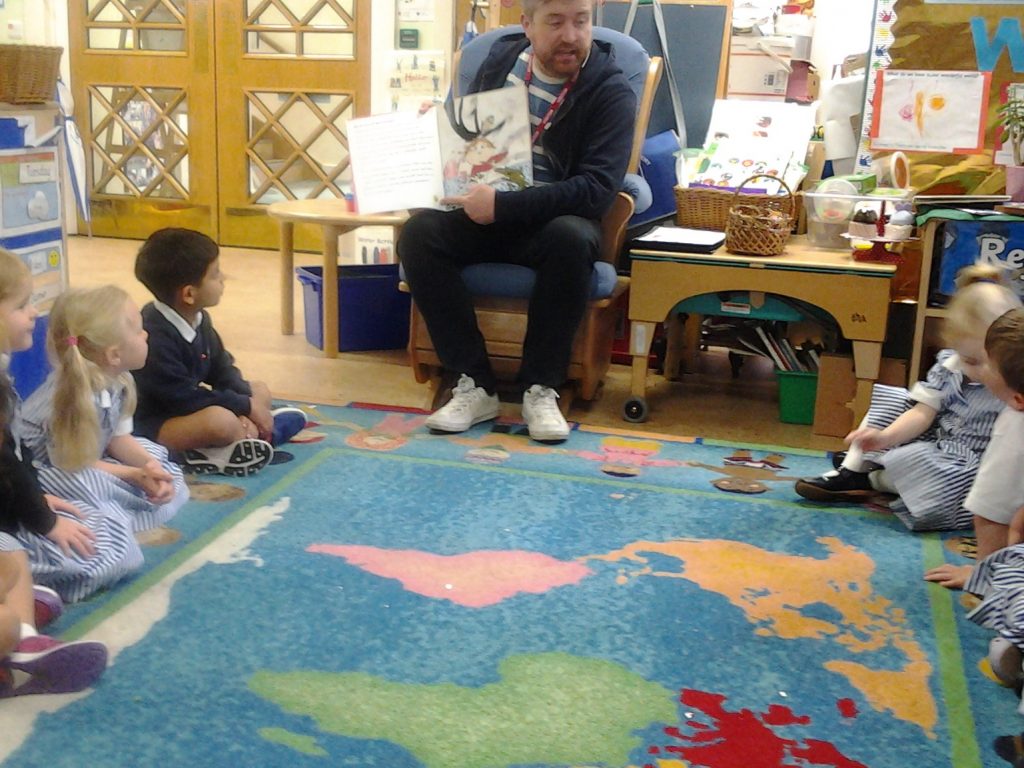

The Church has always viewed education as vital to the formation and development of the whole person and the Bishops decided that the education of the poor was to be the Catholic community’s first priority. At a time when the Catholic Church was in the process of being allowed to fully function again in England there was everything to be done in terms of infrastructure. Tellingly, the Bishops decided to build Catholic schools for the Catholic community before they built Churches. Notably, schools were often used as the place of worship for the parish. Catholic schools continued to be established throughout the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries enabling children from the poorest backgrounds to attend school. In other words the Church chose the education of children and young people above all else. Education had primacy and worth.

It took a further one hundred years until the passing of the Education Act 1944 (also known as the ‘Butler Act’) when ‘secondary education for all’ was promised and increased the school leaving age to 15, meaning that all children from the post-war generation received a minimum of 10 years of education.

When the Catholic Church set about providing education in England for the poor it began a social revolution. Some would say it is time for another revolution and that Catholic schools once again must establish a vision for education at its loftiest so that the brightest choose to teach and where to learn is about depth and not superficiality; where learning has a practical application but where it is also valued for its own sake bringing together centuries of thought on educational theory. It needs to ensure that each of us is enabled to live full lives, to contribute, to work and learn, to grow in the widest sense so that each of us has a compass by which to steer. As social systems change and the cohesion which closer family, religious and face to face networks provided is removed, schools are becoming the nexus of that ethical, social and emotional training. Schools remain places where human presence is sustained. Schools are therefore becoming the offline, real time places where young people learn how to be themselves and how to relate to others.

Far away from extended families, we live in an age dominated by online content. Here parents consult anonymous people they have never met on websites for advice about where to send their children to school. Most of us follow the lives of total strangers on line, led through the byways of related links or pop-up videos provided by Facebook. In this context, newspapers, conventional journalism and learning achieved through careful study is being eroded. With this a quality of thought, which we used to take for granted is being challenged.

Social media saturates every casual moment. Our presence online is measured and rated and organisations email us to tell us how we can improve the chances of being viewed by people we don’t know and didn’t know we needed to know. There is nothing new in a fascination with others and communities have always relied on others to provide a source of analysis, commentary and entertainment. Jane Austen pointed this out in Pride and Prejudice – Mr Bennett knew he made sport for his neighbours. Jonathan Swift also observed this in his novel satirising human perspective. Gulliver observes, “I may add..that my Presence often gave them sufficient Matter for Discourse.”[2]

However when Swift was writing he was referring to a physical presence which has been replaced by the notion of an online presence – something akin to the supernatural presence attributed to saints or ghosts. Much time is devoted to alerting young people to the dangers of being courted online by people with false identities. Very little time is spent exploring the impact of nonentities by which I mean an online presence defined by the banal or what Sartre would have called nothingness. His existential suggestion that we are defined by what we do has some resonance. I am not defined by my online presence – other people who dislike me and post vile calumnies against me might have created it. Instead I have to find a way to be – to make sure that this is recognized as a verb – to be is an active process, it encompasses growth and is never limited or limiting. Our educative processes need to account for the fact that we educate the young people physically in front of us as well as the person they think they might be not to mention the other person they might be online. Complex indeed.

Reading, thinking and writing have become so intertwined with social media activity that we have learned a new language. We speak of presence on social media. In 1620 tr. Boccaccio Decameron II. vii. ix. f. 50, we read “Such dalliances are..fitter for the priuate Chamber, then an open garden, and in the presence of a seruant.” There is a lovely sense in this quotation that presence is a corporal matter and that it involves witness. Boccaccio is separating public and private space. In an age where servants saw most things he was still seeking some privacy. A contemporary online presence supposedly sets up those privacies but the walls are thin and moveable; settings can be changed overnight without us noticing. The servant watches us all the time now. Teaching integrity and truth has never been more important.

Reforms to the curriculum across the board mean that primary children are learning to spot features of grammar of incredible complexity. How useful feature spotting has ever been is a matter of debate when meaning is arguably what matters. The curriculum doesn’t worry too much about semantics. Thus our Key Stage 2 children will tell you that here is an adverb of place. This adverb has expanded in meaning to encompass an abstract online presence but what does that mean? Where is here? To whom am I present when online? We refer to content – a common noun used to denote concrete information. We are told we must populate sites with content. With this language drift we have shifted culturally and philosophically. Is content the same as knowledge?

Subjects have always had syllabuses with required material to be covered. When I started teaching the A Level English Literature syllabus was printed on an A4 sheet of paper folded in half. It had a few paragraphs outlining the number of texts to be covered and the desirability of covering differing literary periods. We set off for a two-year course with no guidance whatsoever beyond libraries of wider reading, examiners’ reports, academic conversations in the staff room and high hopes. The downside of the simplicity of this was that we knew no more than that. It was well documented that up to 50% of candidates failed and this was not therefore a good thing. Along came curriculum 2000 and transparency, a system designed to enable success. We did succeed and results improved. As time went by they improved so much that government became suspicious and ordered that A Levels should be made harder. Teachers have never had a problem with teaching difficult materials, where they are really struggling is with the obsession with Assessment Objectives, curriculum reform without vision, hoops not hopes. Most teachers are merchants of hope – and this optimism needs to be rekindled. There is nothing attractive about a cynic and as someone said, no-one ever erected a statue to one. Sadly rather than become cynics good teachers are leaving the profession because the human joy in sharing knowledge, enabling a quality of thought in a creative and life-giving way has been eroded. Those of us in teaching still believe in human beings and in the power of good. We want those we teach to become great. We need to help them to be.

[1] A Brief History of Catholic Education in England and Wales, CES

[2] Swift Gulliver II. Iv.x.150

Categories: Whole School