Visit to the World War One Battlefields (1).

In our last Assembly for the week of remembrance, Upper V related their recent visit to the Battlefields of World War One. This was a fitting end to our Assembly commemorations to mark the centenary of the Armistice in 1918 and we here hear about their experiences. As the girls said in their presentation, ‘we all urge you to take this opportunity to go on this amazing visit to fully appreciate the sacrifice of so many young men’.

‘To round off the week of special assemblies in our commemoration of the centenary of the end of the First World War we are here to share with you our experiences of the Battlefields trip which took place from Thursday 11th to Saturday 13th October to the First World War Battlefields in France and Belgium. The school has run this visit many times before. However, this year it was very special owing to the centenary of the end of World War I. We spent the three days touring numerous memorial parks, visiting museums, seeing real trenches and visiting a number of cemeteries remembering those who were lost in the fighting. It was a very poignant visit which really helped us to find a much better understanding of how significant the effects of the war were on the people and it was a trip I’m sure we will never forget.

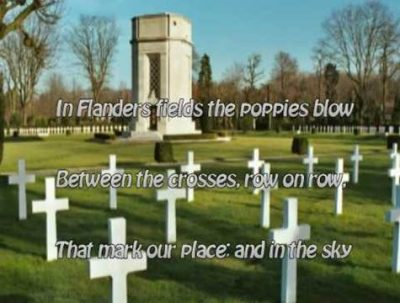

One of our first stops on Thursday was the Thiepval Memorial in the Somme, in France. It is devoted to the Battles of the Somme and to the missing British soldiers. The memorial commemorates more than 72,000 men of the British and South African forces who died in the Somme sector before 20th March 1918 and have no known grave, the majority of whom died during the Somme offensive of 1916. The British army lost almost 19,000 soldiers on 1st July alone, with over 39,000 wounded; this was the heaviest loss of British troops in any conflict before or since. The memorial looks over the Somme River where some of the heaviest fighting took place. It towers over 45 metres in height, dominates the landscape for miles around and was designed by the British architect, Sir Edwin Lutyens. It is the largest Commonwealth memorial to the missing in the world. One of the amazing features of this memorial is that it is designed in such a way that allows visitors to see all of the names engraved. It is on the site where parts of the battle of the Somme were fought and so those who are buried nearby are buried where they fell, both British and French soldiers.

After staying the night at our accommodation in Ypres (known by British soldiers as Wipers) in Belgium, we visited Tyne Cot, a memorial and cemetery in Ypres. Tyne Cot is the largest Commonwealth War Graves Commission cemetery in the world. It is now the resting place of more than 11,900 servicemen of the British Empire from the First World War. This area on the Western Front was the scene of the Third Battle of Ypres. Also known as the Battle of Passchendaele and was one of the major battles of the First World War. For a lot of us, this stop was very poignant as it displayed the gravity of the number of people who died fighting in one small area.

The battle of Passchendaele is memorable not only for the colossal loss of life but also for the fact that the whole battlefield turned into a mud bath when fighting began – many soldiers died not through fighting but by drowning in the mud.

Siegfried Sassoon was an English poet, writer, and soldier. Decorated for bravery on the Western Front, he became one of the leading poets of the First World War. At the end of a convalescent leave, Siegfried Sassoon declined to return to duty and the Under-Secretary of State for War, Ian Macpherson, decided that he was unfit for service and had him sent to Craiglockhart War Hospital near Edinburgh, where he was officially treated for shell shock, now more commonly known as PTSD. Before his treatment for shell shock at a psychiatric hospital he wrote ‘Declaration of a Soldier’ in which he angrily protested against the British government’s conduct in the war. Here is an extract from a poem written by Sassoon.

Memorial Tablet

Squire nagged and bullied till I went to fight,

(Under Lord Derby’s Scheme). I died in hell—

(They called it Passchendaele). My wound was slight,

And I was hobbling back; and then a shell

Burst slick upon the duck-boards: so I fell

Into the bottomless mud, and lost the light.

Sassoon’s letter was forwarded to the press and read out in the House of Commons by a sympathetic member of Parliament. The letter was seen by some as treasonous or at best as condemning the war government’s motives.

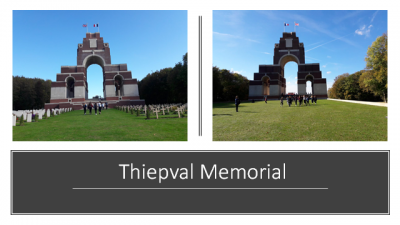

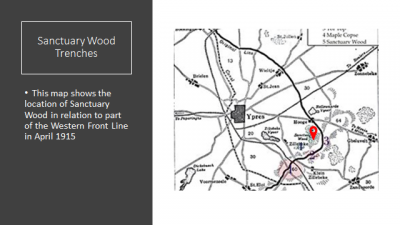

We visited the trenches at Sanctuary Wood on Friday, just outside Ypres, where the original British second line trenches from the war have been maintained. This was a unique experience into seeing trench life and warfare, minus the horrible conditions the soldiers there had to endure. The museum at Sanctuary Wood also displayed an eclectic mix of objects, from post war war-games to a stuffed rat and uncensored 3D photographs which were considered too graphic to be published in books or newspaper articles.

This map shows the location of Sanctuary wood in relation to part of the Western front line in April 1915.

Trench Conditions

While we were there, our tour guide Alan explained the terrible conditions of the trenches including:

- Waist-high mud, which could cause trench foot,

- Rats – who frequently tried to bite sleeping soldiers,

- Lice, which would infest the soldiers’ uniforms causing them to be very uncomfortable and itchy. Lice could cause trench fever, where the soldier developed a high fever, headaches, aching muscles and sores on the skin. It was painful and took around 12 weeks to recover from.

Later that day, we went to the Passchendaele Memorial Museum, where we walked through both British and German trenches. Here we could visually see the differences between the trench systems of the two sides. Both sides used sandbags, wire mesh, and wooden frames to reinforce the walls and wooden planking, referred to as duckboards, to prevent men from standing in water.

However, British trenches were built as temporary structures, using prefabricated corrugated iron roofs buried under sandbags and earth to construct their dugouts. This was because they were fighting an aggressive war – trying to gain back land from the Germans. Whereas the Germans built strong entrenchments, using concrete to construct their dugouts and digging deeper trenches than the British, as they were fighting a defensive war. Therefore, the German army was very difficult to defeat. This is one of the main reasons why the war reached a stalemate and why a war of attrition was fought on most fronts for almost four years, leading to unimaginably high casualty figures. By the end of the war it is estimated that 700,000 soldiers died from Britain alone and 20 million died in total.

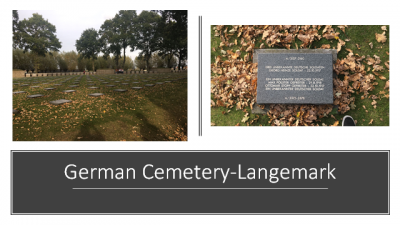

On Friday, we briefly visited a German cemetery – Langemark. It was in vast contrast to the British ones since it was on Allied soil, so the Germans had rented the land from the Belgians – the Belgians, understandably, were reluctant to grant the Germans much land after having been invaded by them. As a result, it was filled with mass graves due to the lack of space that they had been given to bury their dead. The gravestones were dark and had no individual messages like the British ones. This created a very sombre atmosphere in stark contrast to the British cemeteries, which were deliberately designed to provide solace and comfort to the bereaved, as well as to value every lost life equally.

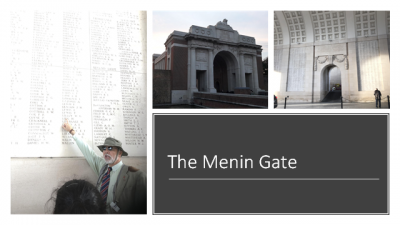

On Friday afternoon, we had some free time in Ypres before the Last Post ceremony at the Menin Gate. It is dedicated to the British and Commonwealth soldiers who were killed in the Ypres Salient of World War I and whose graves are unknown. This is where the Last Post ceremony takes place.

The Last Post ceremony has taken place at the Menin Gate memorial every single day since its opening in 1927, only stopping during the occupation of Ypres by Germany during World War Two. Every evening at 8.00pm the road which passes under the memorial is closed and they sound the Last Post. During the ceremony, individuals or groups may lay a wreath to commemorate the fallen. Lucy Williams and I were lucky to lay down a wreath on behalf of St Augustine’s Priory. This was an amazing opportunity which I am sure we will remember for the rest of our lives.

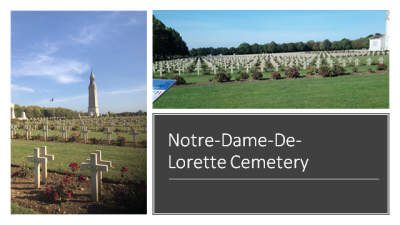

On Saturday, we went to a French cemetery, which was quite different to the British ones.

Instead of the unknown soldiers having their own individual graves they were buried in mass graves. All soldiers whose names were known had a cross on their grave unless they were Jewish or Muslim, where instead they had either a gravestone with the star of David or one facing towards Mecca with the Crescent Moon and Star symbol. None of the gravestones had personal messages like the British ones.

The Memorial, Notre-Dame-De-Lorette, was erected so in a peaceful Europe we can remember a tragedy which devastated a generation of young men. The memorial pays tribute to the memory of all soldiers, from all countries, who fell in the Nord and in the Pas-de-Calais between 1914 and 1918. It had 580,000 names listed in alphabetical order without any distinction made between rank or nationality, former enemies, or friends side by side.

Many of us looked for our own names and were alarmed by the number of people who shared the same surname who had lost their lives in just this one area of France.

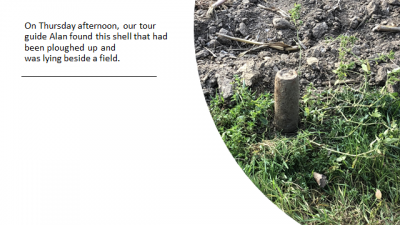

On Thursday afternoon, our tour guide Alan found this shell that had been ploughed up and was lying beside a field. Shells like this are still found today, and are often still live. Many people still get injured today from live shells on the one hundred year old battlefields.

We had all learnt how many people died in the war in class, however, when we saw the endless number of graves, that number meant so much more to us. If we could take just one thing away from the trip, it would be a deeper understanding of the war and of the immense impact it had on the world’s young generation of brave men.

We understand that this assembly may be just like the textbooks – us telling you numbers and showing you a few pictures. However, we all urge you to take this opportunity to go on this amazing visit to fully appreciate the sacrifice of so many young men. We would like to thank all the teachers who took us on the trip, (Mr Murphy, Mrs Sumpter, Mr Elder, Mr Ferguson and, especially, Ms Trybuchowska, for providing us with this eye-opening experience. We will always value the long-lasting effect it has had on us.’

At the end of their beautiful presentation, the girls asked that everyone bow their heads for the prayer

Dear Lord,

We pray for the souls of those who gave their lives for their country. We pray for their families and that they are with you in heaven. We pray for anyone fighting in any wars today, give them courage to stand up for what is right and bring peace to them soon.

Amen’