Oscar Ricketts and Alfred Evans.

Last Thursday’s Assembly continued our series on Ealing people during the First World War. Presented by Mr Elder, English Department, this Assembly told us about Oscar Ricketts and Alfred Evans – two of the conscientious objectors who refused to fight in the conflict.

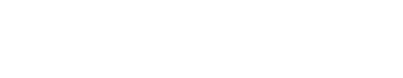

‘What happened to this group of men?

They were arrested and charged. Handed over to the military authorities they were exposed to the shame of being handcuffed in the public streets and railways; confined to a cell and fed on only dry biscuits and water.

They were sentenced to death, which was later reduced to ten years in prison.

These men were British – the prison camp they were held in was in Britain. They were arrested because they refused to take part in World War I – they were Conscientious Objectors. Among them were two local men – Oscar Ricketts and Alfred Evans, both from West Ealing.

A conscientious objector is a person who refuses to join the armed forces because they think that it is morally wrong to do so.

The number of conscientious objectors who passed through the tribunals during the course of World War I was approximately 16,000. There were three categories of conscientious objector recognised by the government’s system:

- ‘Absolutists’: men who were categorically opposed to the war. These men were unwilling to perform any form of alternative, non-combatant service that might aid the war effort.

- ‘Alternativists’: men who would perform alternative work as long as it was outside of military control.

- ‘Non-combatants’: men who would join the army but on the basis that they were not trained to bear arms.

Mr Elder then called us to answer the following questions:

‘If you were called on to fight…?

- What parameters (who, when, why and how) would you set around killing in wartime?

- How would your justification for taking human life apply to the issue of capital punishment?

- What is your position on killing in war? Does your position change in response to certain wars (Iraq, Afghanistan, World War I, World War II, etc.)?

- If our country is attached, how should we defend our families and ourselves?

Ultimately:

- Will I be able to kill someone in combat?

- In what situations, if any, is killing acceptable?

1916 – 1918

- Conscription was introduced in January 1916, targeting single men after 18 – 41. Within a few months World War I conscription was rolled out for married men.

- Men who were called up for service could appeal to a local Military Service Tribunal. Reasons included health, already doing important war work or moral or religious reasons. The last group became known as the Conscientious Objectors.

- 750,000 men appealed against their conscription in the first six months. Most were granted exemption of some sort, even if it was only temporary.

- Only 2% of those who appealed were Conscientious Objectors. Despite the legacy of this group, only 6,000 were sent to prison. Thirty-five received the death sentence but were reprieved immediately and given a ten year prison sentence instead.

Conscription in numbers:

- 2,277,623: the total number of men conscripted into the British Armed Forces during the First World War.

- 46%: the percentage of all British Army recruits that conscription accounted for over the entire war. 54% were volunteers.

- 135,277: the record number of men conscripted in a single month (June 1916).

- 18 – 41: the ages between which all men were eligible to be conscripted as part of January 1916’s Military Service Bill.

- 56: the age the upper limit was raised to in 1918.

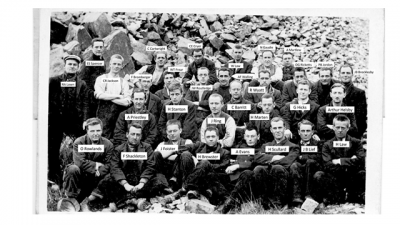

Oscar Gristwood Ricketts of 73 Mayfield Avenue, West Ealing

Why did Oscar object?

‘My objection to war is a conscientious objection based on (1) Religious grounds and (2) Moral grounds.

Religious Grounds.

I belong to no religious denomination, but my religion is a profound belief and acceptance of the teachings of Christ, whose teachings are only comprehensible to me when I think of their root and formulation as being peace and love.

Christ recognised that no matter what the circumstances may be, a man must be consistent, and permit his convictions only, to weigh, as against his interests. He plainly said that -: “Whatsoever a man soweth, that shall he also reap”, so that if a man overcomes his “enemy” by violence , he cannot expect to “reap” peace, since he has sown the seeds of, and indeed even staked his future on, violence. Violence meeting violence can only conceivably breed violence, for the same reason that two natural processes, whether working in harmony or independently, can only possibly produce something natural.

Therefore having allotted my life to a definite pursuance of love and peace, I cannot take any man’s life, or assist somebody else to kill another man. Nor can I possibly allow any kind of circumstances to interrupt or molest the very sacred views which are my spiritual life.

Moral Grounds

War is to me clearly and definitely immoral. That two persons, on failing to agree on a certain point, should immediately commence and endeavour to maim, and even butcher and kill one another, is wholly repulsive to me. I am filled with utter repugnance when I realise that men offer as a means of settling their conflicting opinions, such repellent and forbidding devices as those which are embodied in warfare. How can one, with reason, temper one’s mind with the idea that individuals are doing a right and justifiable thing, when they proceed to hack and mutilate the bodies of their fellow creatures? Such an idea affords me not the slightest reflection that it is even possibly or comparatively moral.

Non-Combatant Service – serving the country by helping in the medical sections or manufacturing ammunition

If I consented to undertake Non-Combatant Service I should be yielding my principles and beliefs up to a huge compromise, and this I flatly and absolutely refuse to do. I could not satisfy myself morally, if I assisted any person so to remedy and prepare his broken health that he might take up again those heinous weapons which do but dislocate and confuse the body. I could not total up those guilty columns of figures, which would be to me but the equivalent of so many tons of shells for the destruction of more bodies. I could not mine-sweep, and so facilitate the passage of some vessel carrying thousands of “guillotines” destined for the slaughter of many many lives. These things I cannot do.

So strongly do I hold these convictions, that, although I may suffer because of them – should your decision be an adverse one – I am fully prepared to take any consequences, however rigorous, indeed, I must take the consequences, as my conscience permits of no alternative. I should like to say that I have held these views since being able to form an opinion of my own.

(Signed) O G Ricketts [aged 21 at the time] 1st March 1916)’

In a peculiar twist, and perhaps with a particularly cruel piece of psychological torture, the army took a number of Conscientious objectors to France ‘If they disobey orders of course they will be shot, and quite right too!’ said Lord Derby, Director of Recruiting. One of the men sent to France was Oscar Ricketts.

The Prime Minister, Lloyd George, quickly said no COs should be killed, but the Army despatched a further batch of men who were told that they were being sent to France to be shot and were marched to the train to the sound of the military band playing the ‘Death March’.

In the early days of Conscription, the Army had no idea how to deal with stubborn, principled men who refused to obey any orders. Bullying and intimidation had failed and in May, the Army stepped up its threat.

By moving the men to France and closer to the front line the Army believed they could intimidate them into submission. If that failed ‘under active service conditions’ they would be free to shoot the COs who continued to disobey orders.

After weeks of painful punishments and constant abuse, the COs – now known as ‘The Frenchmen’ – were formally told: Continue to disobey and face the death penalty. By June, the Army was running out of patience. The Frenchmen were marched out in groups to a camp outside Boulogne within sight of the cliffs of Dover and told for a final time to obey orders. When they refused, their sentence was read out.

Hubert Peet recalled this incident years later — ‘I was number three on the list, and as I stepped forward I caught a glimpse of my paper as it was handed to the Adjutant. Printed at the top in large red letters, and doubly underlined, was the word ‘Death’. I can hardly analyse the feeling that flashed through my mind as I caught sight of the word, ’The sentence of the court is to suffer death by being shot,’ said the Adjutant. ‘This sentence has been confirmed by the Commander in Chief’

There was a long pause

And commuted to ten years penal servitude.’ ie the sentence was reduced to 10yrs in prison

All were given the same long sentence, but they had escaped the death penalty. Prison meant going back to Britain and to civilian prisons. At the last moment, political pressure and frantic work at home by their supporters had saved their lives.

When Oscar had his death sentence withdrawn he was sent to prison to perform manual labour. It was at this prison camp that the photographs that here appear were taken. In 1919 – after the war ended – these men were released from prison. But life would always be hard for them because of the attitudes people had to COs –

Mark Hayler – another CO recalled years later – and like so many other COs he faced problems finding work after release. ‘I was interviewed by committees and the last question was always “What did you do in the Great War?” I knew that was the end. I was offered a very good job somewhere, but the offer was withdrawn: “The whole committee’s very sorry about it, but we couldn’t possibly employ you with a record like that”. No-one would be responsible for employing a man who had been in prison.

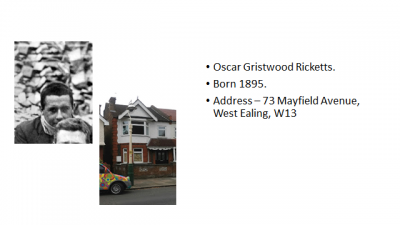

Another local man, Alfred Evans, went through the same process as Oscar Ricketts – he was arrested in Hounslow and sent to prison while his appeal was heard – his appeal was rejected.

Alfred objected on the following grounds: Reasons in support of the application:

Religious and Moral convictions

‘I absolutely refuse to take human life as I consider it inconsistent with the doctrines of Christ.

I firmly believe in the Fatherhood of God, and the Brotherhood of Man, and as God gave me my life I have no right to take it, still less indeed that of a fellow man.

I cannot take the Military Oath.

Signed: A W. Evans Feb 21st 1916’

Notice of Appeal. (Received) 6-3-16. (2) Grounds on which appeal made: I am a Conscientious Objector and absolutely refuse to take the Military Oath. I consider it inconsistent with the doctrines of Christ and absolutely abhorrent.

(Signed: A.W. Evans) [Aged 20]

Being a conscientious objector did not mean being a coward – as this incident proves –

A captain told Alfred that his papers were marked ‘Death’: was he going to continue to resist?

Alfred said, ‘Yes. Men are dying in agony in the trenches for the things that they believe in and I wouldn’t be less than them.’ To Alfred’s astonishment, ‘he stepped back and saluted me, then shook my hand’.

Alfred was one of the men sent to France in attempt to change his mind. In England, before sailing, he was put in the punishment cells at Harwich:

‘completely dark, dripping with water and overrun with rats, for three days without food’. ‘It was impossible to sleep.’ ‘Our guards kept telling us we’d soon be pushing up the daisies, so we weren’t surprised to hear we were going to France – in irons. We were asked to make our wills, but all 17 of us refused.’

From Le Havre we were taken to a huge parade ground at what the army called ‘Cinder City’ and distributed among the thousand or so soldiers lined up there. Military drill began, but ‘not one of us moved.

After that all kinds of tactics were unsuccessfully employed in the attempt to bully or frighten us into obeying orders.

At first we were daily tied by the arms to a kind of crucifix; later on they were roped, face-forward, to a barbed wire fence.

Moved to Boulogne, we were handcuffed with our hands behind our backs in a timber cage roughly 12 feet square, with one toilet bucket between us. After protests such extreme treatment was stopped, but conditions still weren’t good. After a month I went down with dysentery.

All 50 ‘Frenchmen’ were brought together at Henriville military camp in June for court-martialling.

Just before the trials, a captain told me that my papers were marked ‘Death’: was I going to continue to resist? I said, ‘Yes. Men are dying in agony in the trenches for the things that they believe in and I wouldn’t be less than them.’ To my astonishment, ‘he stepped back and saluted me, then shook my hand.’

The sentences were read out in public, in front of thousands of soldiers in formation. Thirty, including me and Oscar, were sentenced to death, commuted in each case (after a dramatic pause in the reading) to penal servitude for 10 years. We were shipped back to Britain, this time to civilian imprisonment.’

At a labour camp in England, a Conscientious Objector called Henry Firth died of pneumonia. The men sang ‘Abide With Me.’ Perhaps the words of this hymn help explain how Oscar Ricketts and Alfred Evans felt about life, the War and God:

I fear no foe, with Thee at hand to bless;

Ills have no weight, and tears no bitterness;

Where is death’s sting? Where, grave, thy victory?

I triumph still, if Thou abide with me.’

In life, in death, O Lord, abide with me.

Dear Lord,

In remembering those who lived through World War One, let us remember the suffering of civilians, relatives and those we might sometimes overlook.

Help us to have faith and courage in difficult times, and guide us to do what is right –

no matter what pressures are put upon us.

We pray that all those individuals that we have heard about rest in eternal peace.

Hail Mary, full of grace,

The Lord is with thee.

Blessed art thou among women

And blessed is the fruit of thy womb, Jesus.

Holy Mary, Mother of God,

Pray for us sinners,

Now and at the hour of our death.

Amen