Alice Harman and Harold and Sidney Medlicott.

Throughout this week we have been commemorating the centenary of the end of World War I at Assembly with our St Augustine’s Priory girls researching some of those caught up in the conflict and presenting them at the Assemblies held each morning.

These Assemblies have been a study of quiet thoughtfulness as the stories of the individuals researched have been presented. The end of each Assembly has been marked by silence as the significance of each presentation has made its impact.

On Monday 5th November Olivia Barnard, Lower V, presented her research on Ealing residents Alice Maud Harman and Harold and Sidney Medlicott,

Alice Harman

‘Alice Maud Harman is the only woman listed on the Ealing War Memorial. She lived at 1 Glenfield Road, West Ealing with her parents and four siblings and was employed at Messrs H. Llewellyn Dent and Co., an engineering works and munitions factory located at Warple Way in Acton. On 23rd December 1916 she was taking her tea break, at about 10.20am. Unfortunately, she was still wearing her oily overalls when she was making coffee on the gas cooker and her clothing caught fire. Her own attempts to douse the flames were unsuccessful. Mr Mills, the foreman, used a fire extinguisher but the flames had taken too great a hold for it to be effective. Finally, another employee, seeing a pail of clear liquid, poured this over her. It was only then that it was realised that this was paraffin, not water.

The inquest decreed that this was a case of accidental death. The funeral was well attended and took place a week later at St Mary’s Church. Alice had been a regular worshipper at St Paul’s Church and the vicar said that she had led an exemplary life and her death would be much felt. She was buried at Ealing Cemetery amidst a multitude of floral tributes. She was 24 years old.’

There were many other dangers of working in the munitions factories:

Canary Girls/Babies were munitions workers whose job was filling shells and were prone to suffering from TNT poisoning. TNT stands for Trinitrotoluene – an explosive which turned the skin yellow of those who regularly came into contact with it. The munitions workers who were affected by this were commonly known as ‘canaries’ due to their bright yellow appearance. Although the visible effects usually wore off, some women died from working with TNT if they were exposed to it for a prolonged period. Everything that the powder touches goes yellow. All the girls’ faces were yellow, all round their mouths. They had their own canteen, in which everything they touched turned yellow – chairs, tables, everything.

Workers in a munitions factory.

As well as handling the hazardous TNT powder, munitions workers risked their health in other ways in the busy, dangerous factories. The working conditions varied, but they often featured poor ventilation, exposure to harmful chemicals and sometimes even asbestos; and the physical labour involved – which included lifting heavy shells and operating machinery – could be back-breaking or extremely risky.

The working day for a munitions worker varied according to where he or she was employed but, owing to the pressures and demands of war production, they generally had to work long hours. Usually a shift system operated, and some workers also put in overtime. The length of time the shifts lasted were not standardised but could be up to 12 hours’ long, as many factories operated both day and night. Many munitions workers later remembered how exhausting the night shifts were and the difficulty of staying alert when working them.

Despite such a tiring working day, munitions workers didn’t have many – or particularly long – breaks. Some even remembered having no breaks at all. The better factories provided canteens, washrooms and toilet facilities for their employees, but these were not to be found at every workplace. ‘From 6.00am to 5.30pm, standing all the time. We had a 10 minute break, to go to the toilets, and we had to stand and eat sandwiches at the machine.’

At the start of the First World War, there were strict controls in Britain over the types of jobs that women could have. But the increasing need for more men in the armed forces meant that these had to be removed, so that women could take men’s places in the workplace. Although women were already able to work in factories, the types of jobs they carried out changed with the move from a peacetime to a wartime economy. There was often some resentment as women began to take over what was seen as traditionally ‘male’ work. Some of the ‘munitionettes’ experienced hostility from their male co-workers, and there was resistance to them earning the same wages as men.’

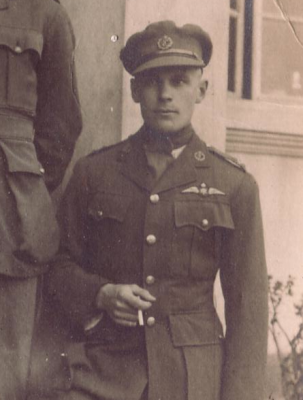

Harold and Sidney Medlicott

‘Harold ‘Houdini’ Medlicott escaped from prisoner-of-war camps at least 10 times. Prior to being imprisoned, he was one of the early Royal Air Force’s leading fighter pilots and his repeated escapes made him a hero to other prisoners. In 1911 the Medlicott family were living at 45 Colebrook Avenue, Ealing. There was cigar buyer John, his wife Laura, and their three children Harold, Sidney and Winifred. Sometime before 1915 the family moved to 20 Granville Gardens, Ealing Common.

Born in 1893, Harold William Medlicott enlisted with the Royal Horse Artillery at the outbreak of war in August 1914, aged 21, and soon rose to the rank of corporal. In September 1914 he transferred to the Royal Field Artillery and obtained a commission as a Second Lieutenant.

On 10th November 1915, Harold, together with his observer, Arthur Whitten Brown, left on a reconnaissance flight to Valenciennes, within German-held territory. Two other aircraft from their squadron escorted them but turned back when enveloped by rain and snow. Instead of following them home, Medlicott and Whitten Brown decided to go on alone, but then suffered engine trouble. They were forced to make a landing behind German lines and were immediately captured and sent to a prisoner-of-war camp at Claustal.

From the moment he was captured, Harold’s thoughts of escape possessed him and he made repeated attempts, despite receiving severe and brutal punishments each time he was recaptured. Often, bad luck was his undoing because several his daring escapes almost paid off. Cutting wire fences in broad daylight, climbing through windows, jumping over walls and hiding in rubbish being carted from the camp were some of the methods he used. As he was repeatedly moved to new camps, only to escape again, Medlicott gradually became an almost legendary figure among the prisoners. He was known as the man who had escaped more often than any other, and he appeared almost impossible to confine. He was equally well known to the Germans, including junior ranks of staff at camps to which he had never been sent.

After serving a term of imprisonment, Medlicott and fellow prisoner Captain Joseph Walter were warned by the camp commandant that if they should achieve the impossible and get out of the camp they would never return alive. Undeterred, it was from here that Harold made his final escape, again with Walter. They were recaptured more than 19 miles away and brought back to a railway station near Bad Colberg.

According to the Germans, they were shot while attempting to escape from the station on 21st May 1918, but the British were not convinced by this version of events. Two days later the dead bodies of Medlicott and Walter were returned to the camp.

In the winter of 1914/15, at the age of 17, Sidney Neville Medlicott enlisted with the 2nd Battalion Middlesex Regiment. Soon afterwards, he obtained his commission as Second Lieutenant to “A” Battery, 61st (Howitzer) Brigade, Royal Field Artillery, in support of the Guards Division.

He fought and died in the Battle of Loos (25th September – 14th October 1915) in northern France. The battle was one of the major British offensives mounted on the Western Front during 1915 and marked the first time the British used poison gas in the war.

Sidney, aged 18 years old, was mortally wounded during the battle and died on 6th October. He is buried in Chocques Military Cemetery, north-west of Béthune.’

Categories: Senior Whole School